Tony Davidow, CIMA® Founder and President, T.Davidow Consulting, LLC

“Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.”

― Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

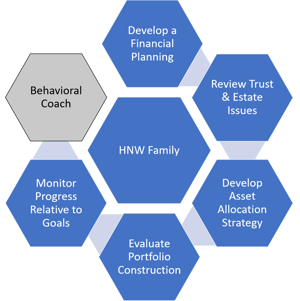

As the markets soar to new highs, erasing the impact of the global pandemic, investors contemplate whether it is too late to get in the market. Investors have a fear of missing out (“FOMO”). Just a few months ago, fear and panic were the dominant emotion. One of the underappreciated attributes of an advisors is serving as a behavioral coach – protecting investors from reacting to their behavioral impulses.

After the market plummeted from late February to late March, investors were tempted to exit the market because fear was the dominant emotion. The DJIA experienced its 7 largest daily point losses during this time period. However, after the market bottomed on March 23, we have seen a dramatic reversal fueled by aggressive Fed policy and unprecedented Fiscal stimulus.

If investors exited the markets in mid-March would they know to return after the bottom? Regretfully, the answer is likely a resounding ‘no’! it is nearly impossible to time when to exit the market – and doubly hard to time when to return.

Behavioral Finance

Behavioral Finance

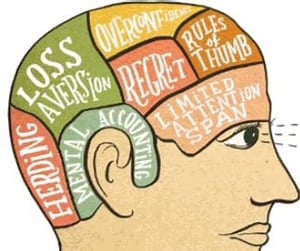

Much of traditional financial theory is based on the assumptions that individuals act rationally and consider all available information in the decision-making process and that markets are efficient. Behavioral finance challenges these assumptions and explores how individuals and markets actually behave. Behavioral Finance studies the biases and traps that we all fall into when we allow our emotions to override the rational reaction to events.

Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky described many of these investor biases in the book Thinking, Fast and Slow. They note that there is often a tug-of-war between our analytical brain and our emotions.

Cognitive and behavioral researchers have identified several common biases that affect investing including:

- Loss aversion. Kahneman and Tversky famously studied how investors will go to great lengths to avoid losses. In fact, they quantified the relationship between loss aversion and seeking gains as 2:1. Intuitively, we see that with investors when there is elevated volatility. Of course, not all investors exhibit the same level of loss aversion and it may vary given the prevailing market environment.

- Confirmation bias. People are often drawn to information or ideas that validate existing beliefs and opinions. They seek a confirming point-of-view validating their position. Obviously, this can be harmful in effectively and objectively evaluating a strategy or investment product.

- Mental accounting. First identified by behavioral economist Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago, mental accounting occurs when a person views various sources of money as being different from others. Money earned may be viewed differently than money inherited, and investors may become emotionally invested in individual stocks or mutual funds.

- Recency bias. Investors are prone to chasing the ‘hot’ stock, asset class and asset manager. They see the strong recent results and extrapolate those results in the future. Unfortunately, as we have covered in this book, chasing returns rarely works out over the long run.

- Hindsight bias. Investors often comment after the fact that they knew a particular stock or investment fail. Investors and advisors tend to overstate their abilities to predict the future which can lead to excessive risk-taking.

- Herd mentality. Humans are social animals. As much as we pride ourselves as being an individual, we often fall into the track of following the herd - doing what others have done. This effects investors who chase the popular stocks or managers for fear of missing out.

By understanding behavioral biases, advisors may be able to improve their client outcomes. Advisors need to identify these behavioral biases in advance and may need to reframe the way they present information to them. Advisors may also exhibit behavioral biases themselves. Once a behavioral bias has been identified, it may be possible to either moderate the bias or adapt to the bias so that the resulting financial decisions more closely match the rational financial decisions assumed by traditional finance.

Advisors can serve a valuable role by becoming a behavioral coach. Understanding these built in biases and understanding how clients may react to a specific circumstance, they protect clients from reacting emotional.

Advisors earn their stripes during these challenging times. They can assist their clients in making rational decisions and avoiding letting their emotions get the best of them. The emotional roller-coaster is often at odds in making the best decisions. Investors often exhibit the highest level of overconfidence at market peaks, and greatest level of despair at the bottom.

The temptation is to take on more risk when you should be reducing it and heading for the exits when you should be seeking opportunities. Advisors can protect clients from making the wrong decision, at the wrong time, for the wrong reason.

Sticking to your process

Rather than bailing on the markets when volatility rears its ugly head, or doubling down when it’s setting all-time highs, it would be more prudent to stick to your process. Advisors should prepare investors for the inevitable ups and downs of the markets. They should build portfolios designed to weather the volatility and periodically take their clients pulse.

We are all humans and are prone to acting on our emotions. Our brain often sends the wrong impulses and signals. Advisors can help condition investors from responding to every impulse and ground them in adhering to a sound approach. Advisors can serve as a behavioral coach.#

Originally published: tdavidowconsulting.com/blogs/becoming-a-behavioral-coach